HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Measures Against Vacant Houses: Grant-Type Japan Versus Premium on Empty Homes in the UK

By Yasuyuki Komaki

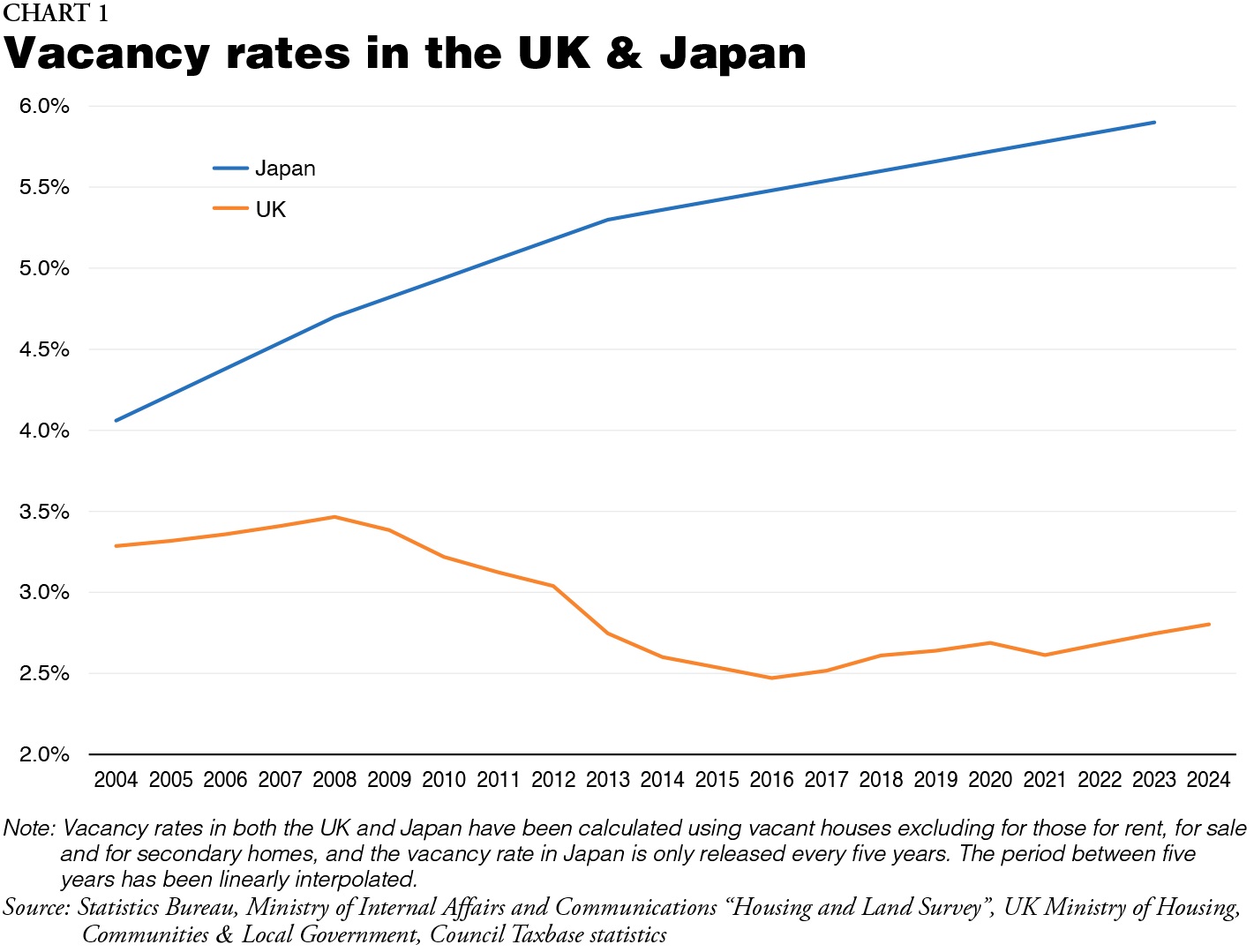

Vacancy Rates in the UK & Japan

The problem of vacant houses is a major policy issue not only in Japan but also in other countries. However, although there are individual case studies on the vacant house problem overseas (Kurahashi, 20131, etc.), there are surprisingly few papers comparing vacant house rates internationally. Although the survey is old, the following is an international comparison of vacant house rates: international comparisons of vacancy rates can be observed in references such as the Nationwide vacant houses management navigation site (2019). Compared to the vacancy rate in Japan, the levels in other countries are lower, and Japan is introduced as one of the countries with the highest vacancy rates. In fact, when comparing the vacancy rates in the United Kingdom and Japan, there are contrasting movements. Looking at vacancy rates excluding homes for rent, for sale and for secondary homes, while the UK has maintained a level lower than 3% for more than 10 years, Japan has been on a consistent rising trend. Further, the disparity in these rates is expanding with Japan at 13.8% and the UK at 3.9% as of 2023.

Low distribution of existing homes and the average life of homes being short are pointed out as the reasons behind the high vacancy rate in Japan. While there do exist special circumstances, the issue of vacant houses has currently become a huge policy challenge for every local government in Japan. From 2023 to 2024, I conducted a field survey regarding migration policies in 157 municipalities across Japan, and as part of this survey I also investigated the housing policies, including vacant houses, of these local governments. In addition, I have been residing in the UK since September 2024 and have had an opportunity to learn extensively about the housing environment in the UK. In this article, I will compare administrative management in the UK and Japan and explore the implications for Japan (Chart 1).

Administrative Management of Vacant Houses in Japan

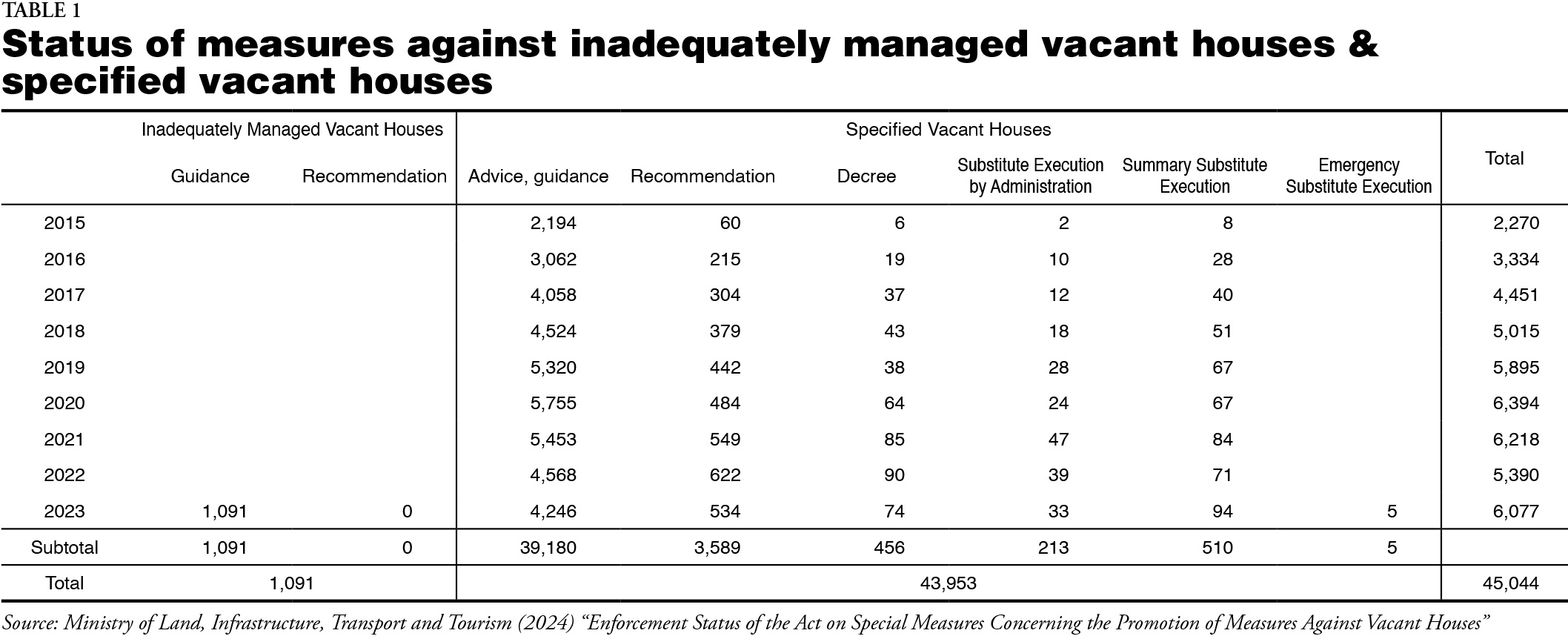

In Japan, vacant houses that come under legal regulations are said to be houses that are inhabitable due to parts of the building being decayed or fractured, or for other reasons. The Act on Special Measures Concerning Promotion of Measures Against Vacant Houses (commonly known as the Vacant Houses Special Measures Act) was enforced in May 2015, and vacant houses are defined as having a building structure or construction work attached to it and its property, with no residential or business usage, and which has been consistently in such a state. Specifically, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism defines vacant houses as being "buildings that have not been inhibited by anybody or have not been used for more than one year". Among these, houses that are deemed to be in a state where they are in danger of collapsing or very likely to pose landscape and sanitary safety issues are classified as "specified vacant houses". Once designated as a specified vacant house, guidance will be issued by the local government on disposal of the house, and if the owner fails to conform to the guidance, the vacant house will be demolished by the administration, and the cost of demolition will be borne by the owner of the house. In addition, once designated as a specified vacant house and issued with a recommendation, it becomes ineligible for "special measures for residential property" and the due fixed asset tax, which was set at one-third or one-sixth of the usual rate depending on the area of land, will be lifted.

In December 2023, the Vacant Houses Special Measures Act was amended, and "inadequately managed vacant houses" was added as a new classification. These are houses that are not fully abandoned like the "specified vacant houses" but are in a state where plants on the property are not managed, litter is scattered, and parts of the building are decayed or fractured. While "nadequately managed vacant houses" is just a designation to prompt better management of vacant houses by their owners, with "specified vacant houses" the government directly intervenes with the owners.

According to references from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 2024,2 such legislation of measures against vacant houses has led to implementation of the removal and/or repair of inadequately managed vacant houses and specified vacant houses, and over 142,000 houses are said to have seen implementation of such measures. However, there are still 235,000 cases of inadequately managed vacant houses, 20,000 cases of specified vacant houses, and approximately 250,000 cases of vacant houses requiring administrative measures (Table 1).

As such, vacant houses which are subjects of the Vacant Houses Special Measures Act are in a terminal state with obsolescence and the risk of collapse. Measures against vacant houses before they become specified vacant houses or inadequately managed vacant houses are not specifically stipulated in the Act. However, even vacant houses in the process of becoming specified vacant houses pose risks for local residents, such as through deterioration of the local environment. In the UK, legal measures are in place before such houses start to become specified vacant houses.

Management of Empty Homes in the UK

In the UK also, empty homes are acknowledged not only as resources that are squandered but also as the subject of complaints and dissatisfaction among the local community and could become breeding grounds for crimes and degradation of the social environment, and just as in Japan, this has become a huge policy challenge. However, measures taken by the government differ greatly.

In the UK, council tax, which is levied based on the appraisal value of the residential asset, is implemented by the local governments. Under the council tax, properties that have been empty for more than six months are defined as long-term empty homes and are subject to an additional tax. Until 2012, homes that were empty for more than one year were defined as vacant homes under the tax system, but as the disadvantages of homes being empty became more widely acknowledged, the period had been shortened.

The additional tax on such long-term empty homes is called the empty homes premium. In England, Scotland and Wales, this tax can be charged to the owners of properties which have been empty, with the aim of forcing the owners to reuse them. This regulation was enforced in 2013 in England and Scotland, and in 2017 in Wales. In addition, in instances when empty homes are used temporarily in order to avoid this premium taxation, reset items have been established. The reset signifies a period during which the house must be occupied. For England, the residency needs to be a maximum of six weeks.

In addition, for homes that are empty for less than six months, the local government conducts tracking and monitoring. This is because there have been instances where complaints were triggered, requiring immediate responses to any public security risk or in cases where the property was under unauthorized access. Further, if the empty homes situation is not resolved even when the empty homes premium is implemented, administrative subrogation will be implemented like Japan.

To provide a concrete example, in Rushcliffe Borough in Nottinghamshire in the East Midlands of England, the empty homes premium is imposed on properties that have been empty for more than one year. However, if the situation is not resolved with just this premium tax, the district council will implement compulsory procedures. Specifically, it will conduct enforced repairs on the empty home and in order to recoup the costs, the subject property will be put up for auction and enforced resale. However, the owners who were passive over the sale of the property can receive the balance of the resale amount obtained at the auction, and there are some cases where an unexpected profit can be made. Alternatively, there is the choice of having the council repair the empty property, which can then be let out for a maximum of seven years to retrieve the costs of repair.

So unlike in Japan, where legal measures are difficult to implement until the property is impossible to inhabit, in the UK, if the house is empty for more than six months, the cost of possession is raised for the owners and empty house management is conducted. The reality in Japan is that current measures for vacant houses which are in the process of becoming specified vacant houses are solely up to the local municipalities.

Measures Against Vacant Houses in Japan Prior to Becoming Specified

Here I will introduce an overview of the field survey I conducted on the status of initiatives against vacant houses by the municipalities (Komaki, 2024)3 along with comparisons with measures against empty homes in the UK. It should be noted that in part, according to the wishes of the municipalities that were surveyed, the names of the municipalities are not disclosed.

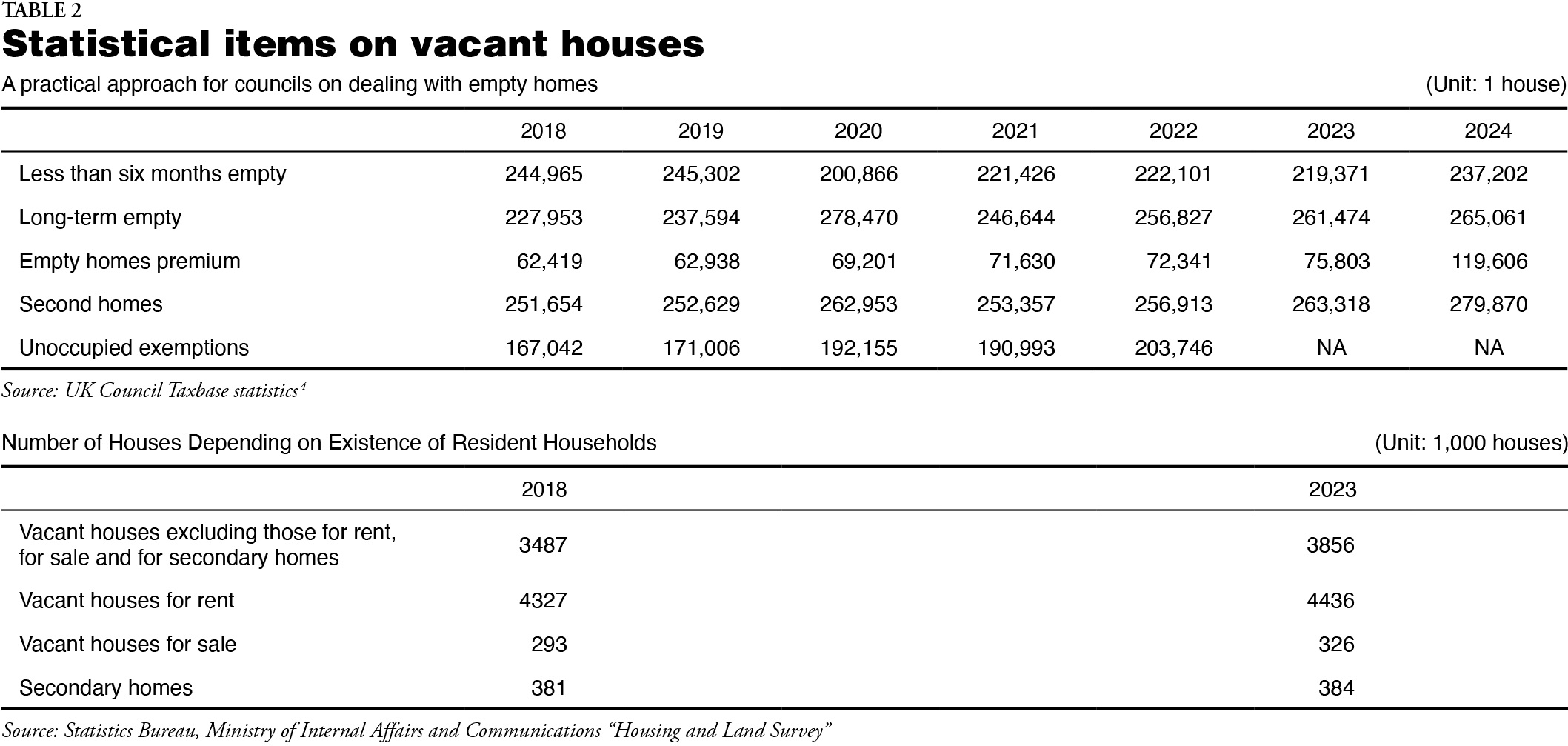

Statistics on vacant houses

Statistics on Japan's vacant houses can be obtained from the "Housing and Land Survey" of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. However, the surveys are sample surveys done every five years. Information on the number of houses such as secondary homes or the number of houses by business types such as for rent or for sale, and decades' worth of information on when the houses were constructed, is available, but results by municipalities are only available for municipalities with a population of over 15,000 people, and information on vacant houses in all local governments is not available for usage. Therefore, in order to conduct effective management of vacant houses, independent surveys conducted by the municipalities are required.

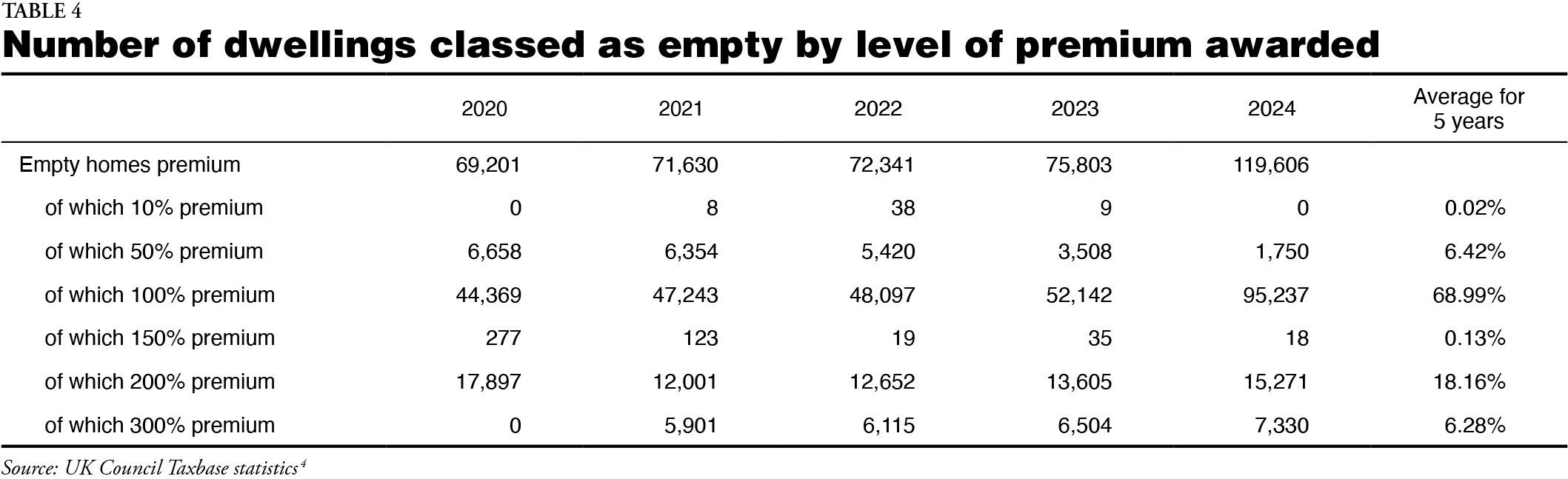

In contrast, council tax data for each of the administrative districts in the UK (https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/council-taxbase-statistics) is available, and aggregated results are released every year. Since premiums are added on to homes that have been empty for more than six months, details on the situation of empty homes by periods can be obtained (Table 2).

Actual state of vacant houses

In trying to assess the actual state of empty houses, field surveys are conducted both in Japan and in the UK. In the UK, empty homes officers are appointed in each administrative district and conduct field surveys. Prior to the surveys, information related to the state of each home, such as information from the local police on the residency status or information on the use of utility fees, is obtained before visiting the field to conduct the survey. Then interview surveys are also conducted with the residents of neighboring houses. It appears that grasping the actual state of empty homes is conducted as part of tax inquiries.

On the other hand, in Japan, field surveys are conducted by staff of the departments in charge of vacant houses at local governments. In particular, while staff of local governments are required to have expert knowledge on real estate transactions, local government staff are on job rotation placements, and thus some local governments place limited-term staff to work full-time on this issue. Depending on the local government also, people such as presidents of neighborhood associations of each village, community activists and migration supporters (citizen volunteers) are utilized instead of local government staff, and they pay individual visits to houses that appear to be vacant to confirm their status.

However, due to a shortage of staff at government offices in municipalities, some local governments do not conduct regular surveys, and there are local governments that have not done surveys at all despite acknowledging the need to know about the actual state of vacant homes. In addition, sharing prior information on vacant house status (information used in the UK such as police information and information on the usage of utilities) is difficult, and the case workers are forced to conduct these surveys by monitoring the exterior of the vacant houses and checking the meters of electricity, gas and water.

Present status of vacant house banks

In Japan, many municipalities operate vacant house banks. Since the relevant local governments are unable to mediate transactions of vacant houses, local and other real estate companies and residential building transaction-related associations conduct these transactions, acting as intermediaries. However, the small number of registrations with vacant house banks has become a big challenge. In particular, Okinawa Prefecture and local governments in the central mountainous regions of Honshu are seeing, in some cases, zero registration despite there being many vacant houses.

As measures to increase registration with vacant house banks, many regional governments, when mailing out the payment slips for real estate tax on the relevant properties, now enclose information on vacant house banks. In addition, there are cases where regular seminars, around three times a year, are held. Moreover, there are multiple local governments which provide an incentive-like subsidy to the owners when a property is registered with vacant house banks.

There is no system similar to vacant house banks in the UK. However, the Local Government Association will share issues among the councils, including the empty homes issue, and fulfils the role of a bridge between the central government and local governments. Members of this association include associate members such as fire and lifesaving authorities, police and crime commissioners, and the national parks authority, and through the National Association of Local Councils (NALC) which is a member organization, town and parish assemblies.

Further, in 2001, the Empty Homes Network was established for officers in charge of empty homes (administrative) across the UK and for practitioners (real estate companies, local community leaders), and works to consider the best method to handle empty homes on a national scale, and sort requests to the government on measures against empty homes.

Measures to heighten closing of contracts on vacant houses

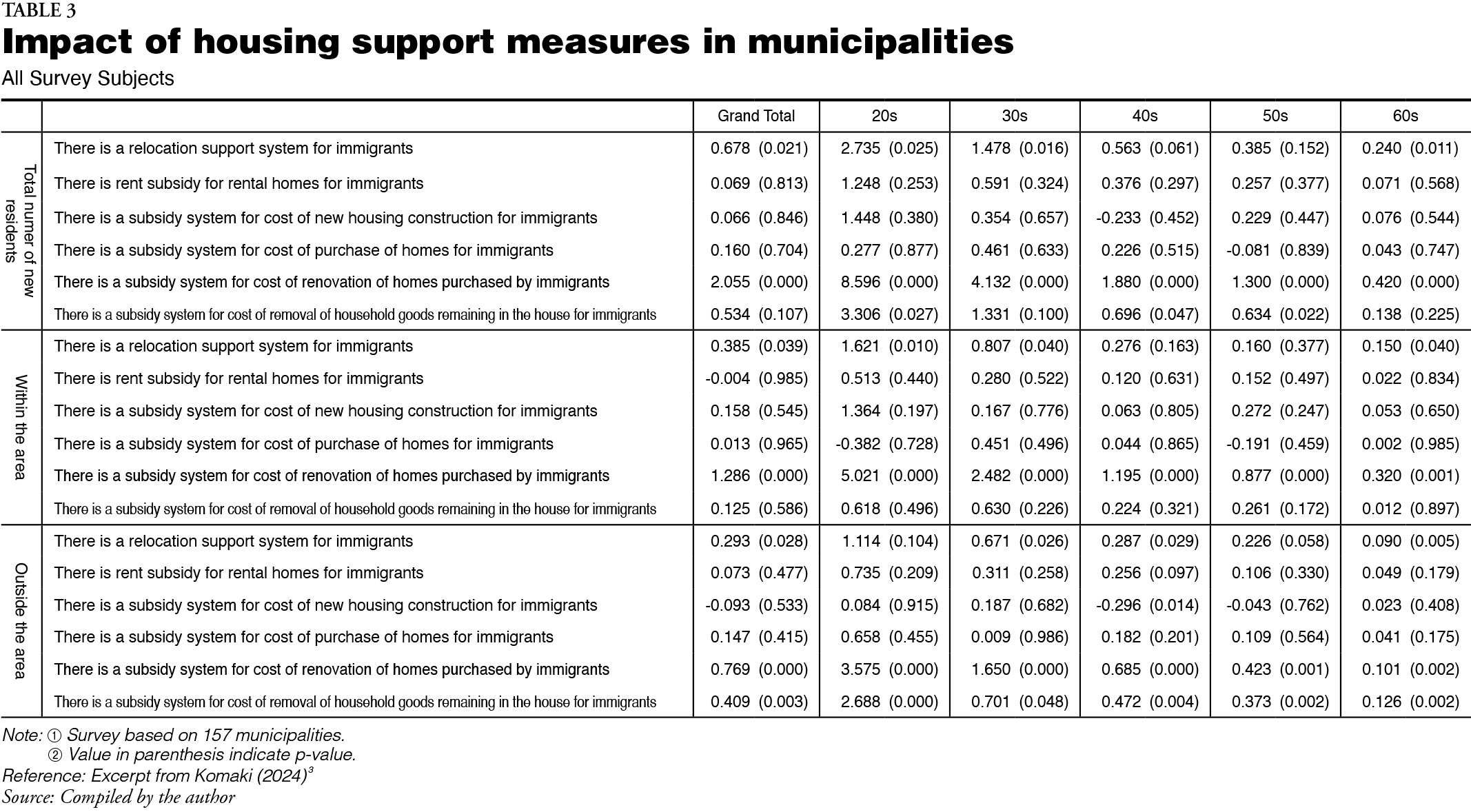

In Japan, working with vacant house banks does not necessarily resolve the issue of status. Thus, subsidy policies have been implemented to maintain and improve the condition of vacant houses, specifically to cover the cost of repairs and disposing of household goods. Those eligible for payments are listed as owners or buyers (renters). The effects of these measures, according to 157 municipality-based measurements, show that this subsidy system is significant, especially for the younger age group (Table 3).

In the UK, as noted, an empty home premium is added to the council tax for properties that have been empty for more than six months. In its application, owners who pay a 100% premium, or in other words twice the amount of standard council tax, account for about 70%. In 2024, it was around 80%. In addition, around 60% pay a premium of 300%. It has been pointed out that this premium system is working and functioning as an incentive to resolve the empty homes situation (Table 4). In fact, the vacancy rate in the UK since 2013 has declined to a level lower than 3% and has been sustained.

For second homes also, with enforcement of the Levelling-Up and Regeneration Act 2023, if the period of usage is short and the homes are empty for a prolonged period, the empty homes premium is imposed, and it is called the second home premium.

Conclusion

The issue of vacant houses is not only an issue in Japan, but is also a huge policy issue in the UK. However, there is a large difference in the measures taken against this issue. In particular, a large difference can be identified in measures against the process in which vacant houses become specified vacant houses. The UK mainly focuses on imposing penalties on owners that are causing the empty homes issue, but in Japan subsidies and other measures are provided to try to improve the status of the vacant house.

It goes without saying that this difference between the UK and Japan is due to differences in the way private rights over land and buildings are perceived. However, in Japan also, certain municipalities are moving to tax vacant houses, including second homes, such as the second homes tax in Atami city or the introduction of second homes tax and vacant house tax that Kyoto city is considering.

Which of these measures is better cannot be determined indiscriminately since there are of course differences in how each of the two countries have evolved historically. However, if resolving the issue of vacant houses is an urgent matter, reviewing the requirements on special conditions for residential land implemented under the fixed asset tax should also be considered. But in order to implement this measure, there is a need to develop statistics on the vacant house situation by specified time periods.

Finally, as a side story, I currently reside in the UK. I often visit my local public library. Here, one can borrow books just as in Japan, but when the return due date has passed, a fine of 20 pence per day (38 yen at an exchange rate of 1 pound=190 yen) is charged. This is just like the private video stores, and this kind of penalty system seems likely to be more acceptable.

References

1. Toru Kurahashi, "Measures for Empty Homes in England", Urban Housing Sciences, No.80, pp.21-24,2013.

2. Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, 2024, "Enforcement Status of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Promotion of Measures Against Vacant Houses".

3. Yasuyuki Komaki, "Regional Disparities in Policies on Residency and Migration, and Verification of Their Impact", FY 2023 Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Statistical Data Utilization Promotion Program, Practical Analysis! EBPM Promotion Program Report, March 31, 2024.

4. UK Council Taxbase statistics, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/council-taxbase-statistics

Article translated from the original Japanese by Mio Uchida

Japan SPOTLIGHT March/April 2025 Issue (Published on March 14, 2025)

(2025/04/21)

Yasuyuki Komaki

Prof. Yasuyuki Komaki completed his doctoral course at the Graduate School of the University of Tsukuba. After working as a researcher at the NLI Research Institute and the Institute of Fiscal and Monetary Policy of the Ministry of Finance and as a professor in the Faculty of Economics at Nihon University, he became a professor in the Faculty of Economics at the Osaka University of Economics in 2018. His book Economic Data and Policy Decisions (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 2015) won the 56th Economist Award.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27