HOME > Japan SPOTLIGHT > Article

Yoga & Vegetarianism in Japan

By Mohan Gopal

In the Ueno area of Tokyo is "Bon", a vegan restaurant specialising in a traditional and exquisite type of Chinese Buddhist cooking, known as Fucha cuisine. It was here over a private lunch that the editor-in-chief of Japan SPOTLIGHT, Naoyuki Haraoka, initiated the theme of this article. Knowing that I am both closely engaged with one of the world's largest yoga organisations, the Art of Living, and am a vegetarian, he asked me to write an article that encompasses yoga and vegetarianism in Japan.

Let me begin with what this article is not intended to convey. It is not an informative list of yoga centers and vegetarian eateries in Japan--a search on the Internet will throw up an extensive lineup of these. Also, as much as I am ever ready to be of assistance to a hungry, Japanese-language-illiterate vegetarian (or vegan) traveling in Japan, that help may not be available to any significant extent here. In short, this essay is not intended to be a survival kit for the fastidious vegan or vegetarian visitor to Japan.

I attempt in this article to weave a tale based on some factual experiences, as to the deeper significance of yoga and vegetarianism in the context of Japan--a bit of the past, some of the present, and what it could harbor for the future.

Terminology--Vegan & Vegetarian

Before I get into the article proper, let me clarify some key terminology. The term "vegan" means a person whose diet completely excludes animal products--that is, dairy items and honey are also off the plate. On the other hand, a "vegetarian" diet is one that eschews eating animal flesh, but permits the consumption of items produced by animals, like milk and honey. Thus, eggs fall in a grey area; many egg-eating vegetarians (including myself) restrict themselves to hen's eggs which in present day supermarkets are, hopefully, infertile. Some cultures make a distinction between animals and fish-- they consider the latter as an extension of plant life and thus an integral part of their otherwise vegetarian diet. In modern times, specific terminology has been coined--at least in the English language--to accurately classify each type of vegetarian. An ova-lacto-vegetarian is one who eats egg and dairy products; a pescetarian is a fish-eating vegetarian, and so on. Many airlines go into considerable detail to describe their in-flight catering options, though, in spite of choosing carefully, the passenger may be sadly surprised to see something different during mealtime. Many a time, even though I had selected the ova-lacto-vegetarian option while booking, I have eyed the whipped butter and delicious-looking cake on my neighbour's meal tray with mouth-watering envy, as I reluctantly consumed the margarine and vegan oatmeal cookie I had been served instead. Far better of course than finding a piece of meat or fish in one's ostensibly vegetarian meal. I understand that this does happen by mistake at times.

In this article, vegetarian means someone who eats neither meat nor fish, but can eat dairy products and honey,

The Concept of Yoga

The word yoga mostly conjures up an image of a lissom person engaged in rather complex body movements. However, it is not so. These physical maneuvers are just one small component of yoga, called yoga asana. In actuality, yoga is a holistic practice encompassing food, breath, meditation, lifestyle, and wisdom, in addition to asana. Yoga is the union of body, mind, and soul. An outcome of yoga is the urge to serve without strings attached and with a joyful mind. Western historians state that yoga was born in India a millennium or two back. However, it may be inaccurate to date the ancient teachings of India based on Western science with its inherent limitations. Indeed, the birth of yoga in India may have been several hundreds of millennia ago, altogether in a different period of the planet's evolution. Sage Patanjali is credited with cognizing this system. There are ancient Sanskrit scriptures--notably the Yogasara Upanishad and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali--which detail the complete requirements for holistic Yoga, including food.

The type of food one eats, the quantity and timing, impacts the quality of yoga. Simplistically stated, a vegetarian diet impacts it positively. The converse is also true. That is, the sincere practice of yoga may inculcate a natural tendency to move away from a non-vegetarian diet. Many practitioners of yoga have experienced this in their lives, even though they grew up on a non-vegetarian staple diet.

A Delightful Vegetarian Cafe in the Woods of Kiyosato

Marina Navashelova ,a long-time resident of Japan, is a yoga teacher of the Art of Living tradition. With the Covid-19 pandemic taking a significant toll on her main travel business, she moved her base from Tokyo to a far more cost-effective location 200 kilometers to the west in Kiyosato, Yamanashi Prefecture. The move for her was a blessing in disguise. With crisp and clean mountain air, delightfully frigid winters and pleasant summers, and bountiful fresh vegetables, the place was a replica of Marina's Siberian roots. Here, she could create her dream vegetarian cafe and both practice and deliver the benefits of yoga in serene surroundings. Over a bowl of delicious vegetarian borscht accompanied by salad and home-baked Russian bread, I enquired about her vegetarian journey. Marina said that as she dived deeper into holistic yoga, an inner strength to surmount problems developed, along with a natural inclination to become vegetarian, without any qualms about leaving behind the non-vegetarian diet she had grown up on (Photo 1).

As of date in Japan, there are about 50 certified teachers of the Art of Living holistic yoga programs. Most of the teachers are Japanese--hence, they were born into and grew up with non-vegetarian food habits. Like Russian-born Marina, they transitioned naturally into adopting a vegetarian diet, being complementary to their yogic pursuit.

A Historical View of Veganism in Japan

Until the end of the 19th century, the Japanese people were mostly pescetarian and eating meat was generally considered unacceptable. Like many other matters, the situation drastically changed in the Meiji Era with a conscious attempt by the government to imitate the West, which was perceived as a role model at that time. As a result, meat consumption increased significantly.

While in modern times the West started developing vegan alternatives due to the number of people following such a diet increasing, Japan continued a very non-vegetarian trajectory with few food options available for a vegan or vegetarian visitor. Time gradually erased the concept of vegetarianism with even Buddhist clergy adapting to Japanese dietary homogeneity. A smattering of temples--primarily in Kyoto, Nara Prefecture and the grand temple of Eiheiji in Fukui Prefecture-- continued to follow the strict tenets of Japanese Zen cuisine (known as Shojin Ryori), but by and large this exquisite and healthy culinary delight was regrettably unknown to the average person. For those Japanese who had heard of it, it was more of an exotic fare to be tried as a tourist to some monasteries in their own country.

Today, there is a small but rapidly growing number of Japanese establishments that see a need for considering vegan options. This need is either driven by a strong feeling that veganism is tied to wellness and sustainability or that it can cater to the burgeoning number of overseas visitors with dietary restrictions, or a combination of both these factors.

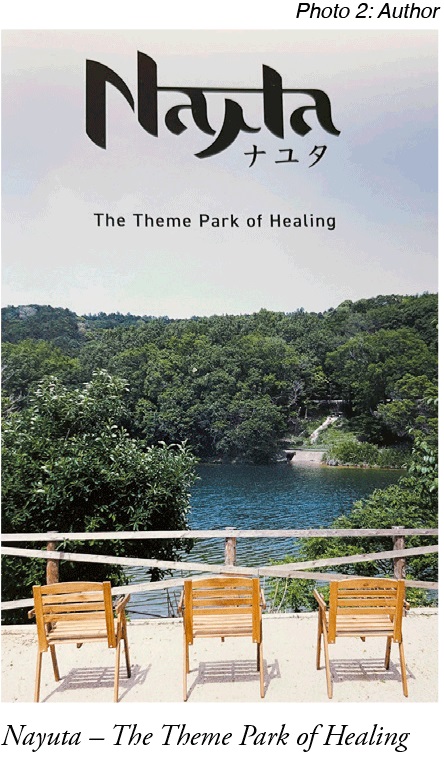

Nayuta --a Vegan Resort in Fukuoka

About 45 minutes from Fukuoka, Kyushu's largest city, towards the hills in the northeast, is Nayuta, a vegan resort. It is a lovely and luscious place, offering space, freshness, tranquillity, and general wellness through strictly vegan and organic food options. The brainchild behind Nayuta is the young CEO, Kouhei Maeda. During his several visits to India, he had been impressed by the yogic traditions and wisdom in that country, including the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Wanting to capture the essence of the wisdom, while at the same time ensuring a sound business proposition, he bought a hot spring hotel which was up for sale near his hometown. The resort--to quote Maeda, "a theme park for healing"--is still in its infancy. Located on an expansive rolling green area with woods and walking paths, it currently includes a spacious architect-designed main building, two vegan restaurants and an organic juice bar, a herb garden and "tent" saunas--a facility resembling the traditional woodfired Finnish sauna (as against the modern versions in Japanese cities with television sets installed inside the sauna chamber). The tent saunas are collectively named "The Vanish"--to signify an atmosphere where one's identity vanishes, leaving one with just one's true self (Photo 2).

A Solution to a Moral Conflict--Vegan Meat

I have mentioned two factors as the primary drivers encouraging more vegan options in Japan. One, is wellness and sustainability; the second is the ability to cater to a wider customer base--especially from overseas. There is yet another reason, which is an original basis to vegetarianism and veganism--the moral standpoint of whether humans have the right to kill another living creature to satisfy their hunger. This thinking is a key factor in the strict traditions of Jainism, Buddhism, and some forms of Hinduism. It also occurs in many other spiritual traditions, though perhaps not on a continuous basis but as a dietary restriction to be observed on holy occasions. In ancient China, monks developed an innovative way out of the conflict between the tongue and morality, by creatively developing meat-like food using vegetable products. In modern times, this has taken the form of vegan meat--products which have the consistency of flesh but are made from soybeans.

I attended a vegan festival in Tokyo recently. I was surprised to see over 70 food booths and by lunch time a lot of the food had sold out. The crowd was large. Were they all vegans/vegetarians? I would say, no, far from it. Except for some foreigners, who may of course have been vegan, it was essentially residents out on a warm spring holiday and savoring an exotic food option. It goes to show that there could be a potential market even among the local population.

A week after the vegan event, I was in Oita in Kyushu to deliver a talk on yoga and vegetarianism to a small group of people at my friend's cafe which uses local organic produce. I was met at the station by one of the participants, Keiko Kawasaki. During the 30-minute drive to the cafe, she mentioned somewhat apologetically that she ran a meat shop in the city. She added that it really was not her preferred choice of business, but an unfortunate family circumstance had led to the current situation. She said that her dream was to engage in the business of food that was healthier and more sustainable, and could be eaten by all who come to Japan. I suggested to her that vegan meat could be the solution and a sound business proposition to boot.

The cafe is in the hills of Oita city on thousand-year-old ancestral lands owned by the brother, Tsuyoshi Kaneko, of my acquaintance. A notice board at the entrance of the cafe announced that it was reserved for the day for a "vegetarian food and yoga" event. The cozy place is run by Kaneko and his elderly mother, acclaimed for both her cooking and warm hospitality in the local community. Most of the vegetables and rice they use are grown organically by them in their own fields. Gazing over these fields, the vegan lunch was a delight. My small audience seemed rejuvenated by the lunch and refreshed by the talk and meditation which followed it (Photo 3).

The Indian Spinning Wheel in Remote Kagoshima

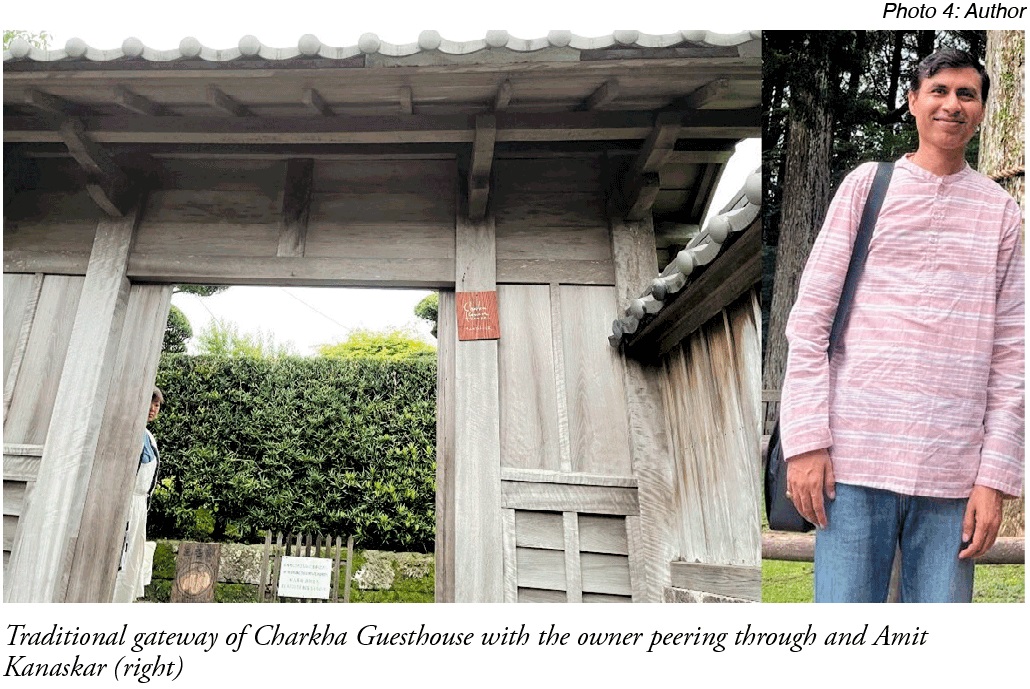

While Fukuoka and Oita prefectures together account for the northern and northeastern part of Kyushu, at the southern extremity of the island is Kagoshima Prefecture. It consists of a tail-like archipelago extending southwest through the South China Sea up to Okinawa, and a main crab-shaped peninsula on Kyushu. The claws of the crab in themselves form a peninsular pair almost enclosing Kagoshima Bay between them. In one of these peninsulas--the Satsuma Peninsula--is the historic area of Chiran, and it is here that Indian-born Art of Living teacher Amit Kanaskar purchased an old Japanese house with the intention of using it as a base to disseminate the benefits of yoga and meditation to the whole of Kyushu, 1,000 km away from his principal place of work and residence in Tokyo. In his search for vegetarian options there, Amit had chanced upon Yasue Iwasaki. A fan of both India and spinning-looms, she had implemented her passion in the guise of a homely guest house offering vegetarian fare, named Charkha after India's iconic spinning-wheel. The guest house with its ancient gate is in the historic Samurai quarter of Chiran which dates to over two centuries ago. The quarter consists of a half-kilometer-long central street, bordered by two-metre-high rock walls and neat hedges of residences. Unspoiled by telephone poles, overhead electricity lines and vehicles, the area preserves its ancient character (Photos 4 & 5).

It may sound ironic that today the charkha--a symbol of Mahatma Gandhi's non-violent struggle for Indian independence--and a peace park are the hallmarks of Chiran, which was the launching pad for kamikaze fighters in World War II. It is further significant that Amit complements this yearning for peace through holistic yoga. Kagoshima, like much of the Japanese archipelago, is volcanic and it is these eruptions that are the foundation of Japan's bounty of hot springs. Is it again a matter of irony that fury and violence in nature, years later transform into benefits for mankind? Yogis would say that both negatives and positives appear real to us, and when this perceived dichotomy is transcended, one realises what is truly real.

From Chiran, I spent a restful night at the serene Kirishima hot springs, 70 km away.

The Vegetarian of Iihatov

The upper part of the main island of the Japanese archipelago begins about 200 km northeast of Tokyo and stretches for about 500 km before meeting the Straits of Tsugaru which separate it from Japan's northernmost island Hokkaido. The region is called Tohoku, literally, "the northeast". It is regarded as the most inward-looking, rural part of Japan. Unlike their ebullient compatriots in the southwest--especially the people of Kansai and Kyushu--the natives of Tohoku are in general rather shy and reclusive, these traits being more than matched by their naivety, innocence, and innate warmth. The topography of the land alternates between snowy mountains, hills and forests and vast rolling fields suitable for rice cultivation. Winters are hard and long; the short summers are lively. The region is bordered on the west by the frigid and grey waters of the Sea of Japan, and on the east by the relatively warmer and blue Pacific Ocean. However, this coast is not always as pacific as it sounds. A detailed look at the map will show a highly fissured coastline--the sad result of tsunamis caused by earthquakes across thousands of years, the most recent one being the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011. While the largest city in the region is Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture, the largest prefecture is Iwate to its north. In Iwate's central region is the city of Hanamaki, which 100 years ago was home to a great poet, writer and humanitarian and a staunch vegetarian, Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933).

Kenji was born the eldest son of a prosperous business family, juxtaposed against the dire poverty of the local rural community. From childhood this contradiction impacted him and by nature being rather devoid of an appreciation of the realities of business, he chose a path far removed from the riches which could have been his. A brilliant scholar, he had a passion for learning, was a prolific poet and writer and an educationist. He had a deep interest in nature, the universe and all its constituents, ranging from plants and planets to rocks and animals. It was this adoration of life in all its forms which moved him to eschew killing and become vegetarian--a feat at any time in Japan and more so a century ago. Several of his stories do portray killing, though in a rather quixotic way. For example, in "The Restaurant of Many Orders" two hungry travellers get lured into a haunted restaurant and then themselves become the prospective meal for a few magical wild cats who had created the eatery with the objective of satisfying their own hunger. However, my take on this is that Kenji wanted his readers to understand the terror of being killed, which he was certain animals experienced when they came under the butcher's knife.

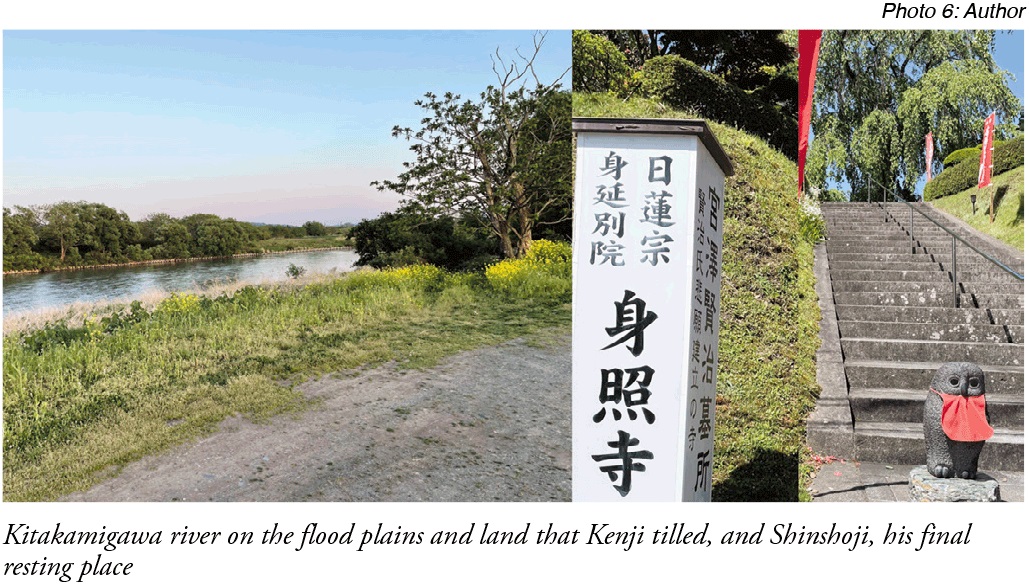

Much against the wishes of his father, he also developed a passion for the Nichiren sect of Buddhism and became an ardent follower. Poignantly, his father finally accepted Kenji's passion a few years after his demise. He had his beloved late son's remains transferred to the Nichiren temple Shinshoji in Hanamaki and himself converted to the sect.

Kenji was fascinated by the landscape of his home province. With his fervent imagination, he visualised a utopian land which encompassed Iwate and the sky and stars above, a land where all life is respected. He named this country, Iihatov. Many of his stories and poems are based here. Kenji also held a deep compassion for the downtrodden and this prodded him to even engage in the physical work of a peasant in the fields that he loved. Unfortunately, his physique was hardly suitable for any kind of physical labor. He had had health problems from childhood, and this combination ultimately contributed to his death at the age of 37. His swan song--discovered and published posthumously--sums up his life. Respect all; avoid anger, desire nothing; pray for a strong body to be able to serve incessantly--and let nothing defeat you in this endeavour (Photo 6).

Hanamaki breathes Kenji. As an integral aspect of this, I was wondering if it would be a vegetarian paradise, but alas, like elsewhere in Japan, the food business revolved around non-vegetarian dishes. That is, until I chanced upon Sobe's Cafe.

Sobe's Vegan Cafe

Sayuri Sobe started her dream business in the year 2000. She decided to return to her ancestral home and continue the tradition of her rice-growing ancestors, but with a difference--her farming and produce would be organic. She would implement her key phrase "Value and Respect Life" and provide healthy vegan food that can be eaten by people with dietary restrictions too. To use her words, "The food here is grown and prepared with a sense of gratitude for the earth's blessings." When I mentioned the purpose of my visit to Hanamaki, Sobe enthusiastically exclaimed, "the spirit of Kenji Miyazawa runs through me." Kenji would have been pleased (Photo 7).

The Future

We can see a vision unfolding--a dramatic vision where the cast consists of people like Keiko Kawasaki, Sayuri Sobe, Kouhei Maeda, Yasue Iwasaki, and the teachers of holistic yoga. A vision of holistic wellness, compassion and a oneness with nature coupled with economic sustainability. A vision where the universe is celebrated. The Iihatov visualised by Kenji Miyazawa embracing Japan.

Japan SPOTLIGHT July/August 2024 Issue (Published on July 24, 2024)

(2024/07/29)

Mohan Gopal

Mohan Gopal is an IT professional living in Tokyo since 1991. He is a multi-culture specialist, teacher and sales coach and is closely associated with global humanitarian organization The Art of Living as special advisor in Japan.

Japan SPOTLIGHT

- Coffee Cultures of Japan & India

- 2025/01/27